Report on the restoration of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting Venus and Cupid

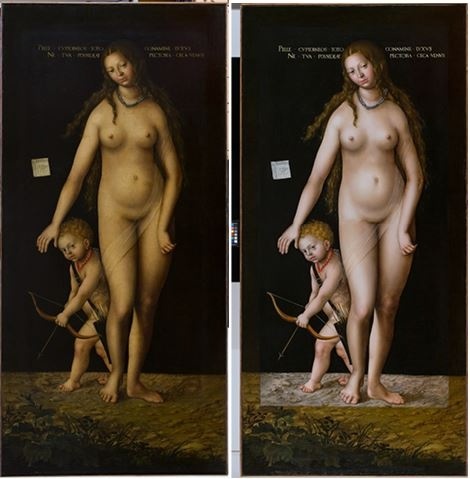

General view after restoration

General view after restorationWork performed:

- obtaining and analysing archive data on previous restorations of the painting

- photographic recording of the painting at all stages of the restoration process

- carrying out technical-technological examination, including a new complete x-ray, infrared reflectography, the study of visible luminescence under ultraviolet radiation, taking and analysing microsamples of varnish, the paint layer and primer – determining the painting’s current state of preservation

- removal of surface soiling

- regeneration of the old varnish

- developing a procedure for reducing the thickness of the varnish and removing overpainting

- reducing the thickness of the varnish, removing overpainting, fine finishing of lacquer and retouching, bringing the surface to a uniform state

- application of restoration primer in areas with losses of the paint layer

- repeat regeneration of the old varnish, now reduced in thickness

- coating the picture with new restoration varnish

- inpainting of areas with losses and abrasions; tinting of parts of the later extensions visible within the frame taking account of the uncovered original paintwork

THE HISTORY OF THE PAINTING:

The painting came into the Hermitage on panel, but with a format already altered due to extensions: 235 × 102 cm, while the original size was 170.5 × 84 cm.

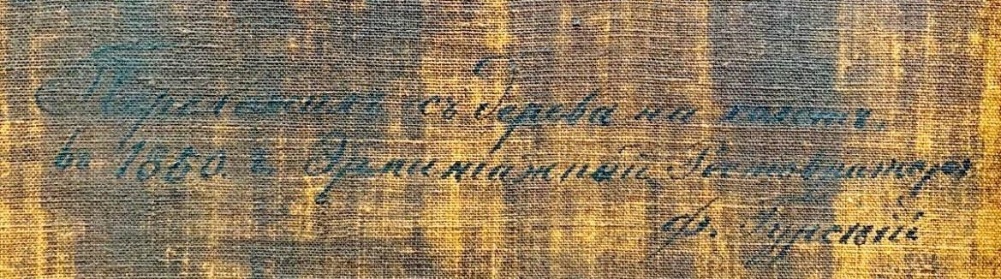

Archive file № 56 “On the restoration of Hermitage paintings 1849–50” contains a “Register of paintings requiring restoration” for the year 1849, with an indication that “L. Cranach’s Venus and Cupid from the 5th storeroom requires cradling.” To all appearances, cradling was not carried out. The painting’s state of preservation did, however, arouse concern and became the reason for the employment of a radical conservative measure – transfer from panel to canvas. The estimate submitted by the restorer Fyodor Tabuntsov on 10 May 1850 states: “№ 358. Lucas Cranach’s Venus and Cupid 24 [square] feet. Transfer, remove varnish and painted corrections. 101 roubles 64 kopecks silver.” (Fund 1, Schedule 2, Doc. 56, 1849, ff. 14, 65). An inscription on the reverse of the picture states: “Transferred from panel to canvas in 1850, Hermitage restorer F. Gursky”. We do not know why they did not go back to the original format during the transfer, but the restoration extensions that were left attached are interesting now as part of the work’s history over the centuries.

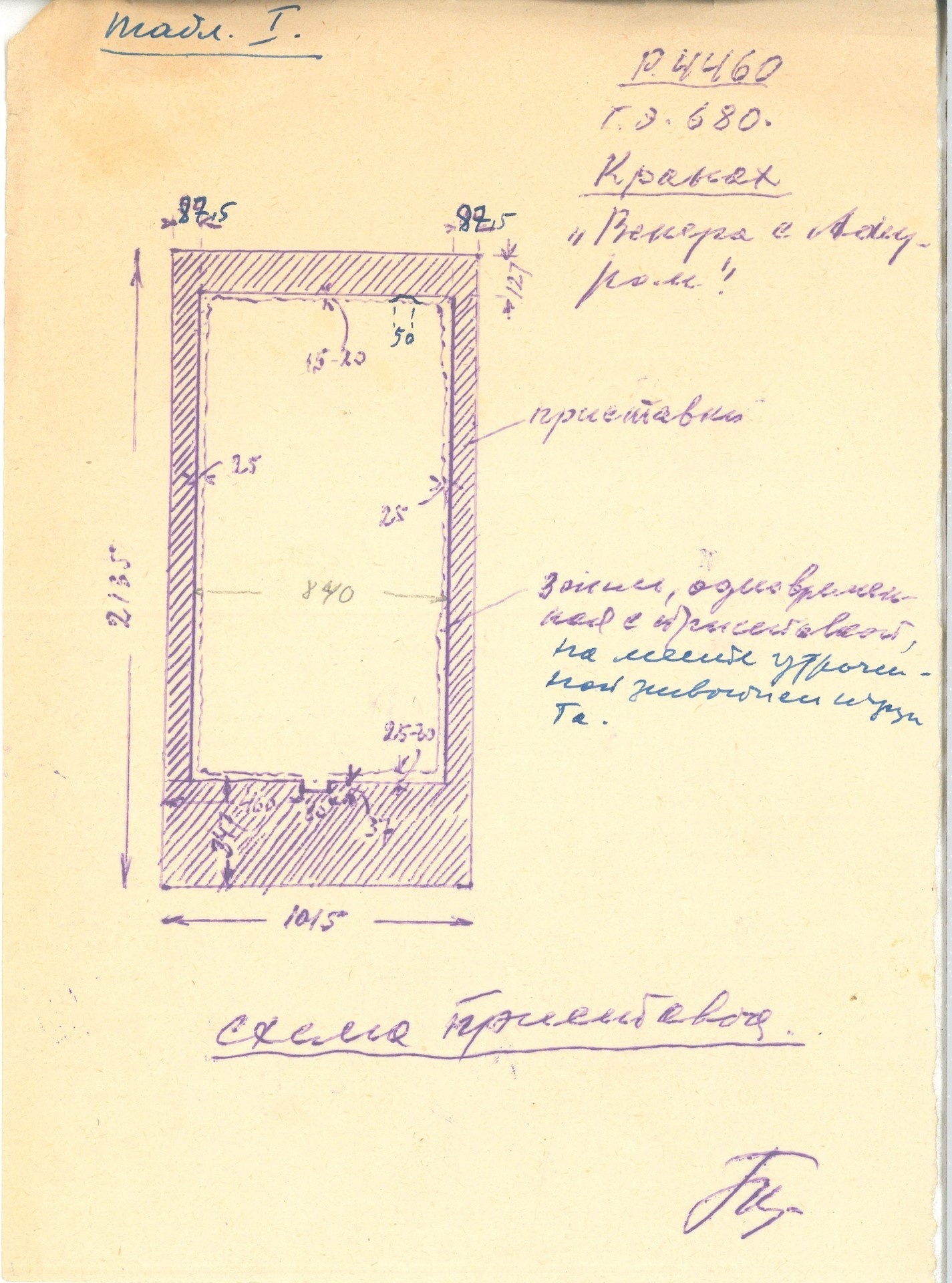

The archive of the Laboratory for the Scientific Restoration of Easel Paintings (abbreviated below to LSREP) contains three records of restoration of the painting: № 4460 (from 1949–50); № 11200 (1972) and № 14067 (1983). The operations carried out amounted to the regeneration of the varnish. However, the distorting effect of yellowed varnish and numerous darkened areas of overpainting was noted regularly since then.

Drawing by P.I. Kostrov. Diagram of the original format and extensions. 1950

Drawing by P.I. Kostrov. Diagram of the original format and extensions. 1950 UV (1950)

UV (1950)

In the course of the 1949–50 restoration, Pavel Kostrov carried out research to determine the painting’s original format, a study which contains some valuable observations and conclusions about the work’s state of preservation. The results were published in the 6th issue of the Soobshcheniia Gosudarstevennogo Ermitazha [Reports of the State Hermitage] for 1954, while from 1953 onwards Venus and Cupid was exhibited in a frame with the later additions masked over.

State of preservation prior to the 2022–24 restoration

The paint layer and primer are in a stable condition. The tension of the canvas used for the transfer is satisfactory and even. This is undoubtedly positive, since traditionally the edges of the canvas were neatly trimmed to the width of the stretcher, preventing any retightening. The expandable pinewood stretcher with double crossbars and shims is in a functional condition.

Conservation is not required.

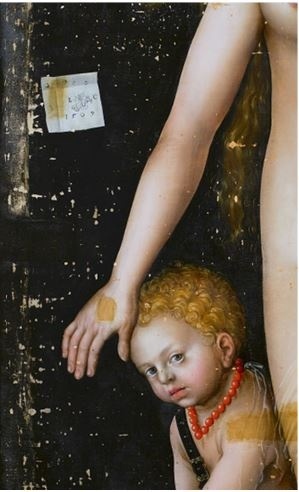

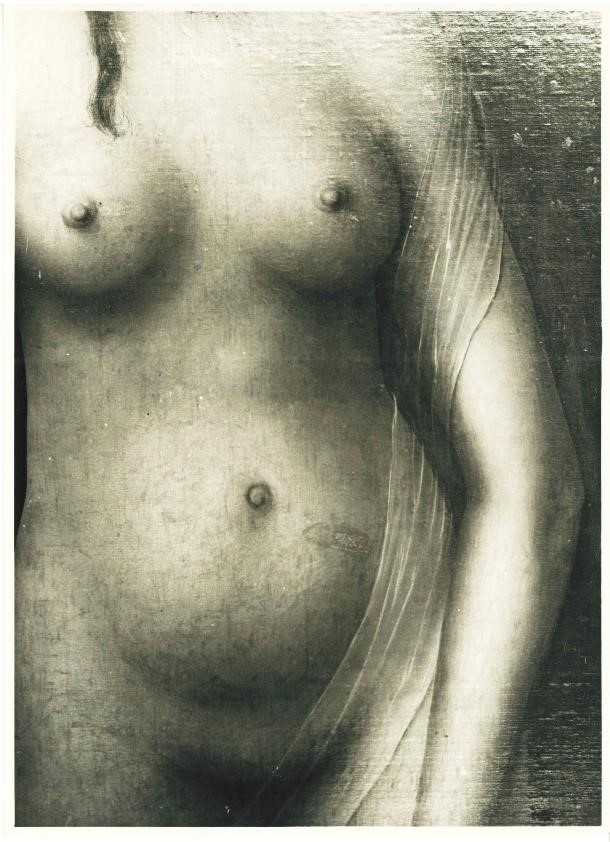

Areas of old overpainting extensively conceal the artist’s original work in the background and can also be seen in the lower part – on the depiction of Venus’s foot and the ground. The deep destruction of the varnish and overpainting on the depiction of the black background regularly manifests itself as the whitening or dulling of various areas. The figures of Venus and Cupid, on the contrary, are wholly covered with “dark sores” of old overpainting and tinting that have changed in colour and tone. A considerable layer of yellowed coating resin is distorting the true colour scheme and obscuring the texture of the work.

Examination

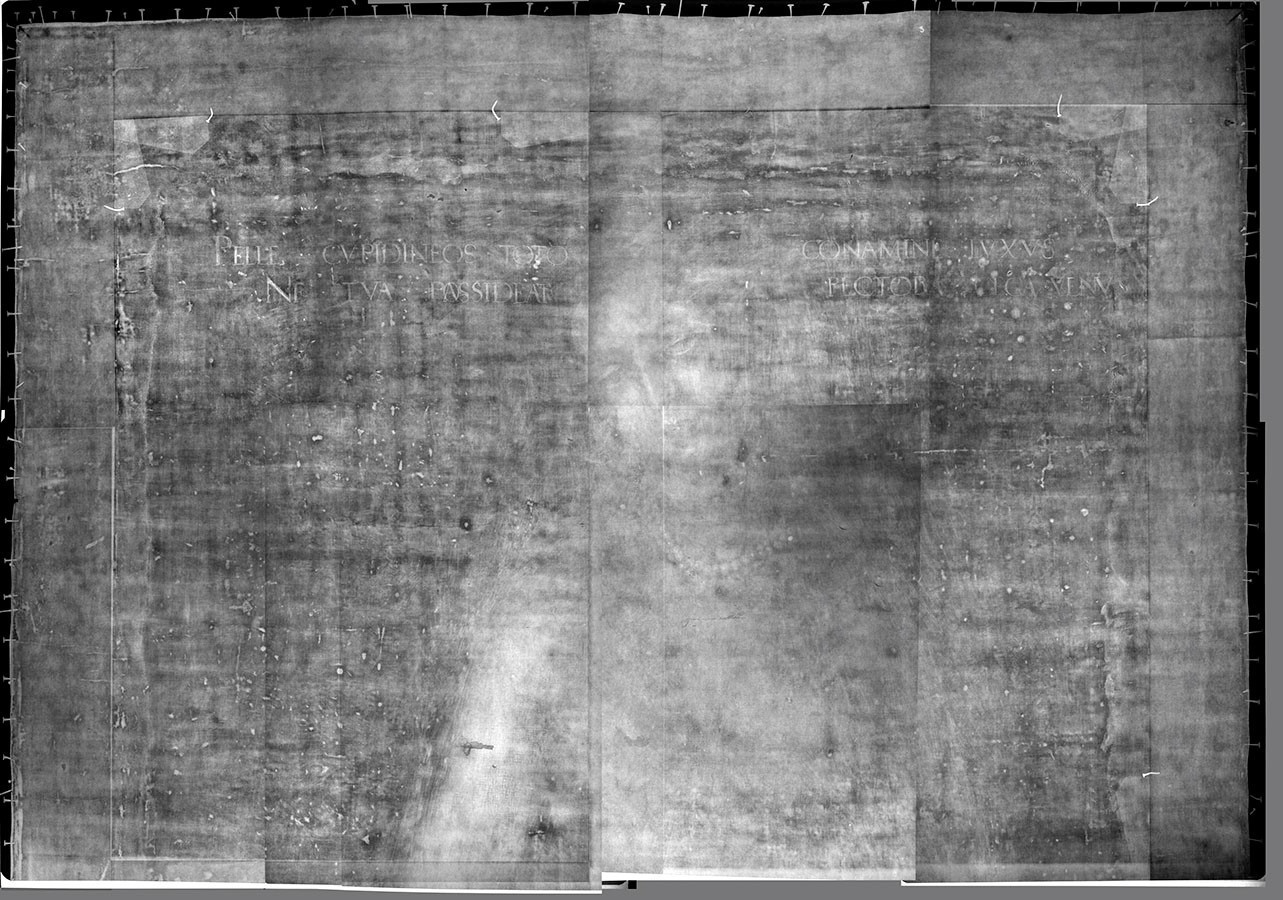

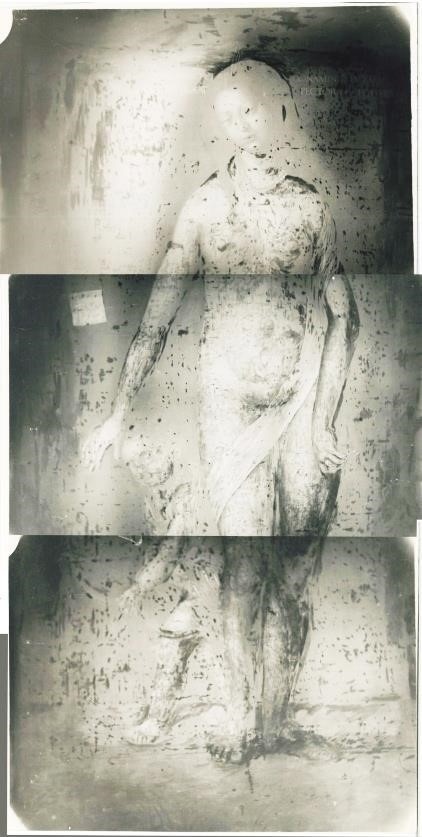

A complete x-ray study of the painting was carried out in the Department for Scientific and Technical Examination by its deputy head, Sergei Khavrin, using 24 sheets of x-ray film. The layer of lead white used in the new transfer primer absorbs x-rays, visually drowning out the fine paintwork also executed with lead white. The results of the study proved short of ideal, but satisfactory: numerous old losses (mainly from the background) were rendered visual, which did not contradict the further uncovering of the work.

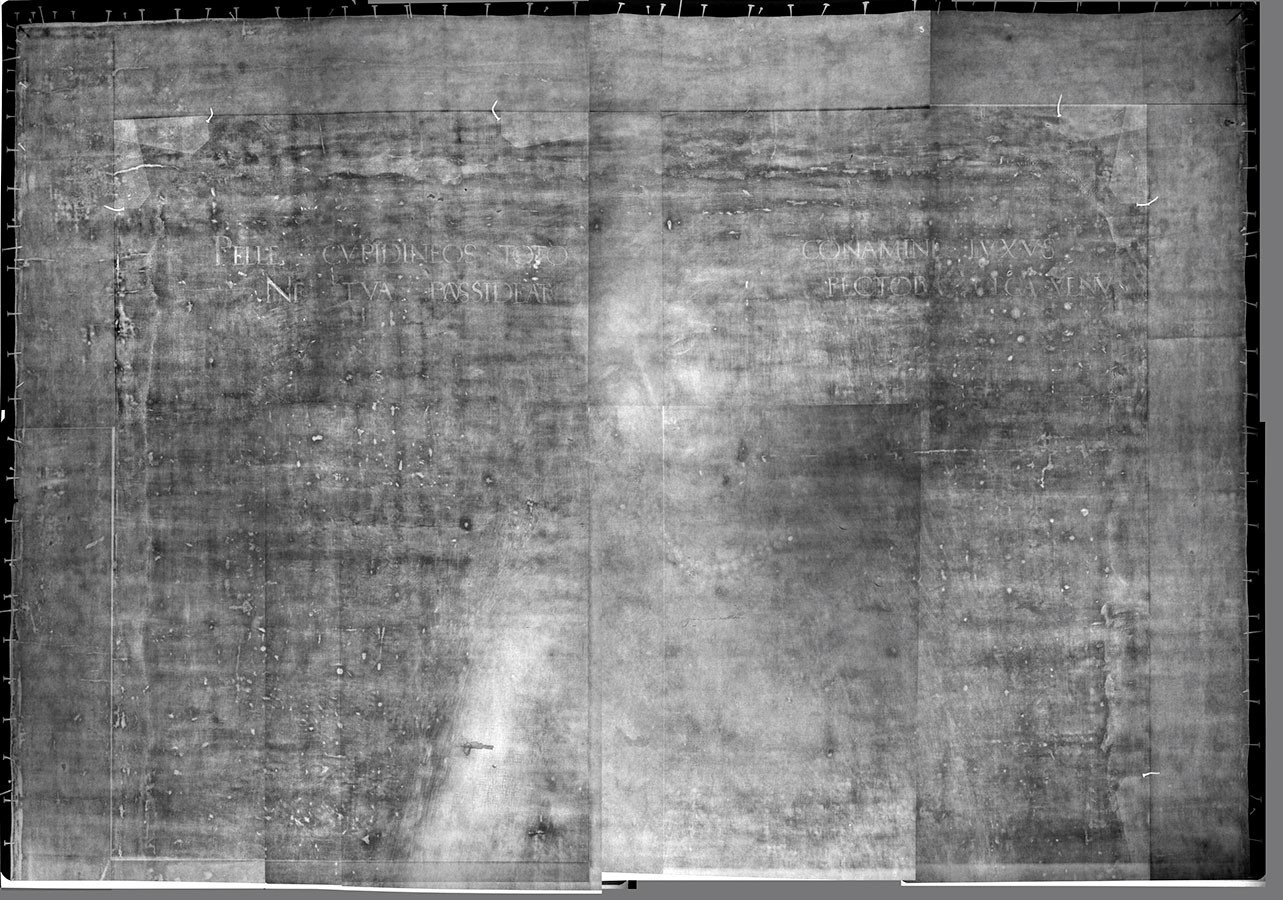

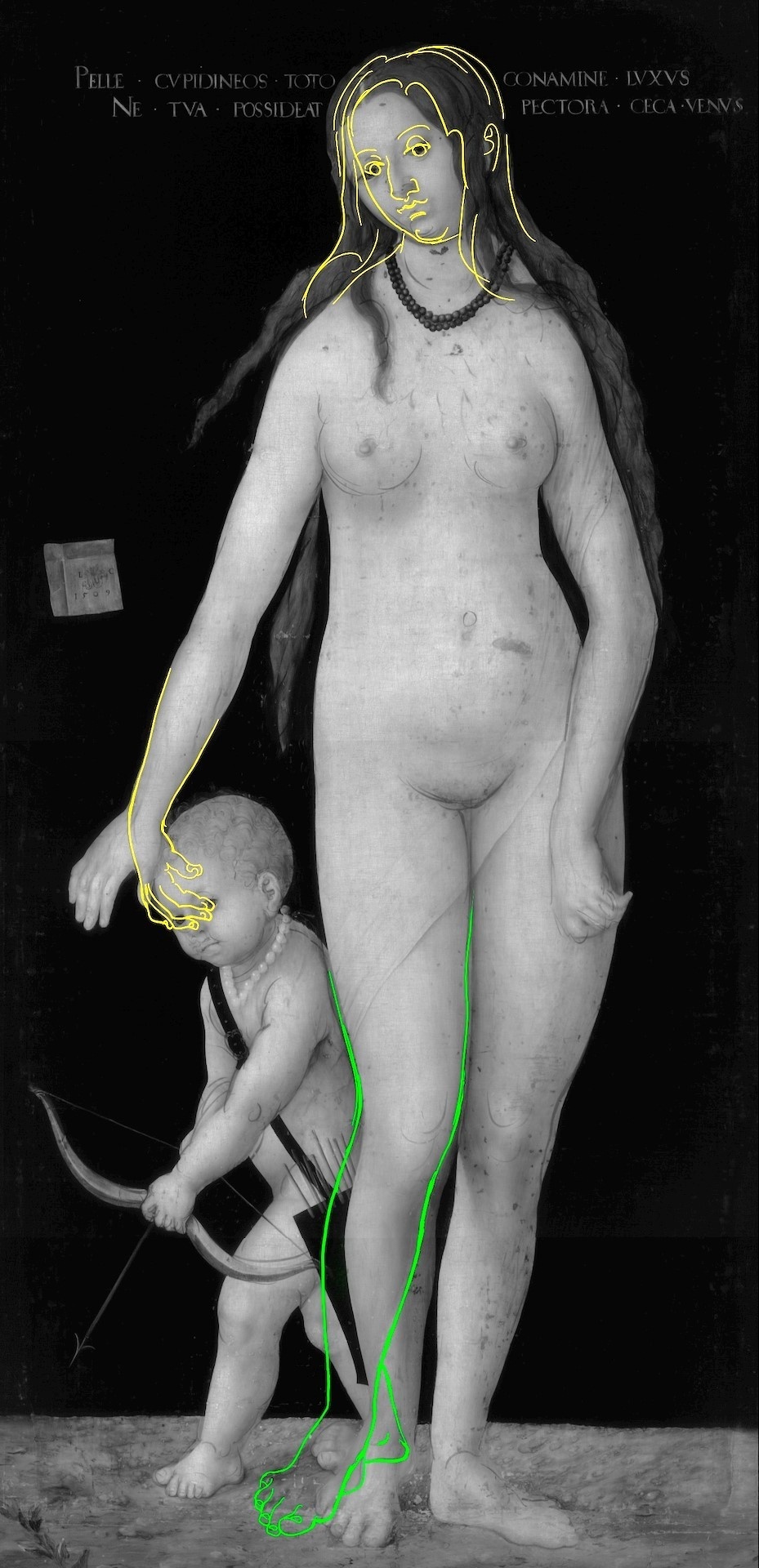

The infrared reflectography carried out in the LSREP before restoration (using an Osiris camera; operational wavelength 0.9–1.7 µm) added to the conception of the process involved in the painting’s creation. The first brush-sketch composition, made in a very free manner, depicts Venus covering Cupid’s eyes with her right hand. Then the artist reworked this illustration of “Love is blind” and altered the movement – Venus is either restraining Cupid’s impulse or else only about to block his vision. Additionally, the turn of the head and the position of the right legs of both Cupid and Venus was changed.

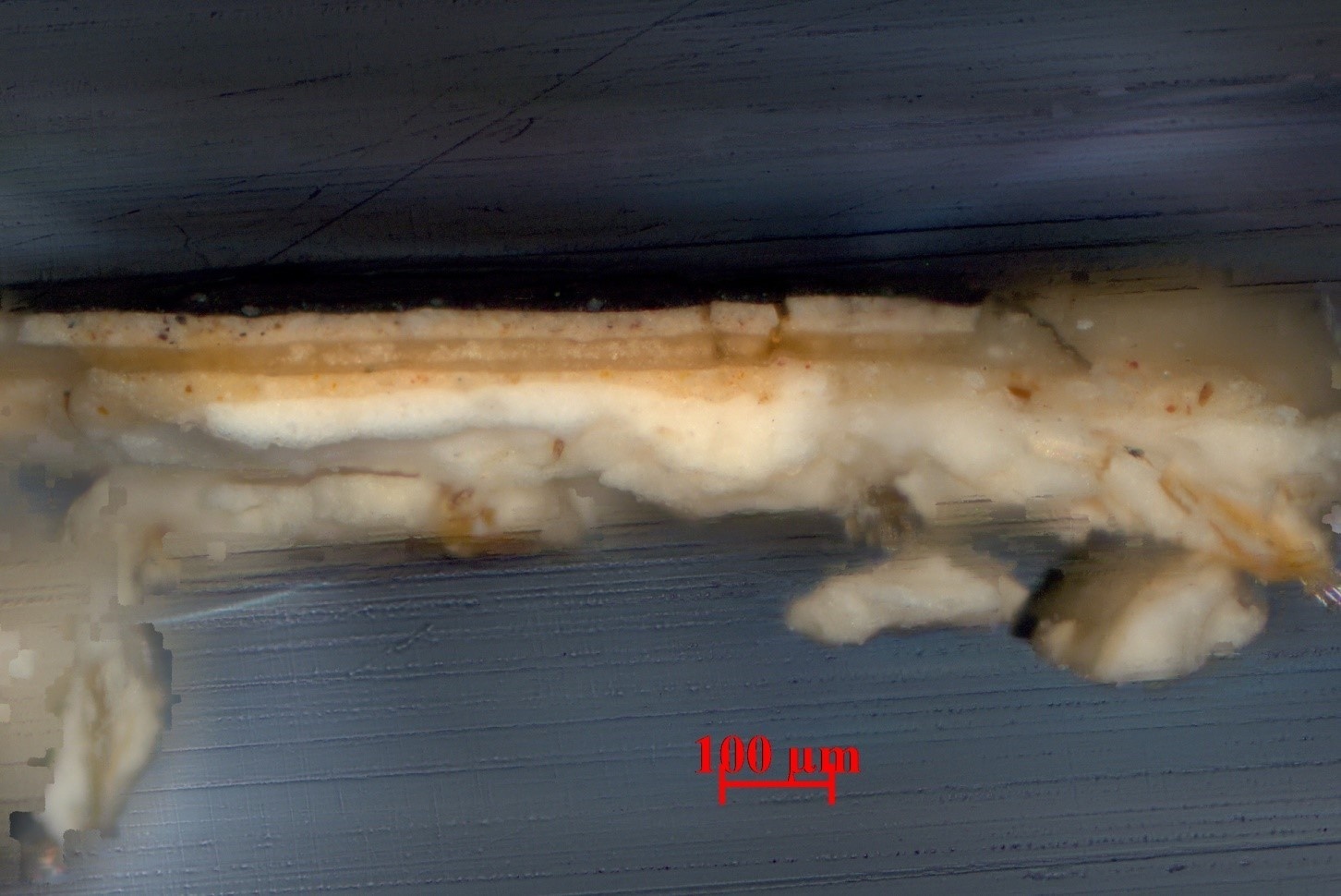

In order to establish with certainty that the legs were repainted, it was necessary to resort to taking samples for microsections. Comparison of x-ray and infrared imaging proved unfruitful since the transfer primer with its lead white content has a strong screening effect. It was proposed to restrict matters for restoration purposes to an analysis of the varnish, but ultimately a broader approach was taken.

Examination of six microsamples (four of the paint layers and primer, two of the varnish) was carried out in the LSREP by leading researcher Kamilla Kalinina using a Hitachi TM 300 with an energy dispersive microanalysis function and a Zeiss Axio Scope.A1 polarizing microscope coupled with an Axio Cam HRc camera working in the visible and ultraviolet light spectrums. The filler in the original primer was chalk of natural origin – remnants of coccoliths were found. The pigments: lead white, ochre, a black organic pigment. The transfer primer is made up of two layers: a lower thick one of lead white, while the upper thinner one varies in pigmentary composition and tone depending on location. Under light-coloured areas of painting the shade is light, under dark ones, correspondingly, dark (Archive of the LSREP, finding № 261).

An analysis of the composition of the binder of the paint layers and primer was carried out on an Agilent 7890 B/5977 gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer. The binder in the paint layers is oil – walnut and linseed.

The varnish mainly contains natural resin (mastic) and oil, with rosin and Venetian turpentine also present. Poppyseed oil was found in the transfer primer. (Archive of the LSREP, finding № 265).

It can only be presumed that the restoration materials date from 1850, although it is difficult to judge how complete the uncovering and retouching of the paintwork was at that time (if indeed it happened as all). It is entirely possible that in this picture we are encountering far older restoration additions dating back to the time when its format was enlarged by adding extensions.

The Restoration

of 2022–24

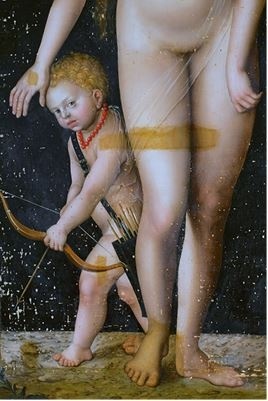

Detail with the artist’s signature in the process of uncovering with a control area of varnish and overpainting. The true black colour of the background emerged only after the varnish was reduced in thickness and the overpainting that gave it a brownish-green tinged removed.

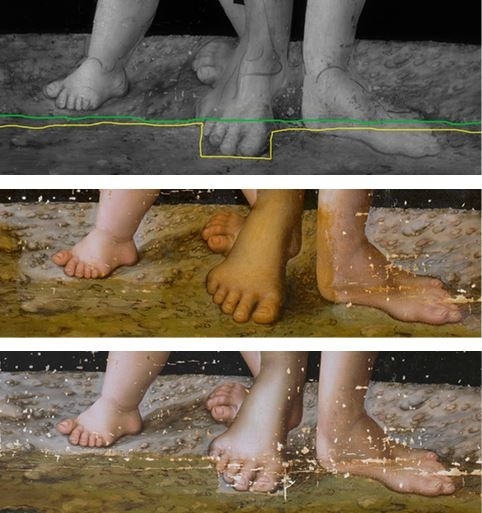

The original depiction of the toes on Venus’s right foot was revealed. Above in infrared, the yellow line shows the outline of the original format, the green the overpainting. The assumption was that it covered a loss and there was no original paintwork below, but the toes painted by the artist were uncovered along with a patch of soil.

The toning process: at the top the losses have almost been retouched, while they still remain below. Since the painting is elongated and fairly large, a rail was required as a support for the maulstick. It was fastened in such a way as not to touch the paintwork.

A working group was formed from the staff of the State Hermitage for the restoration of the painting:

- Scholarly supervisor – Maria Garlova

- Co-ordinator – Yevgeny Feodorov, head of the Project Finance Sector

- Curator – Victor Korobov

- Artist-Restorer – Maxim Lapshin